What happens after a well is drilled, fitted with a hand pump, and a community celebrates having access to clean water for the first time? Half of them break down in a year.

When a community lacks sufficient resources and training, these wells would be rendered unusable; however, a new study by the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill’s (UNC) Water Institute and Water and Sanitation for Africa, a Pan-African humanitarian agency, found that if local water communities collect fees for repairs and train community members to fix the wells, they can remain in use for decades.

The study found that nearly 80 percent of wells drilled by the Christian humanitarian organization World Vision – which integrates local water committees, usage fees and repair teams into its model of delivering clean water – were still operational after more than two decades. The research, funded by the Conrad N. Hilton Foundation, will be presented at the World Water Week meeting in Stockholm, Sweden. The foundation has provided $80 million over more than two decades to enable water access to an estimated 2 million people.

“The results of this study are very encouraging,” said Steven M. Hilton, Chairman, President and CEO of the Hilton Foundation. “Strategic investments targeted at developing the capacity of local communities ensure that water systems remain reliable and long-lasting.”

“The good systems are the ones that are maintained and repaired when they fail,” said Jamie Bartram, Don and Jennifer Holzworth Distinguished Professor at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill’s Gillings School of Global Public Health and lead researcher on the study. “And they can fail and be repaired time and time again for decades.”

Bartram and his colleagues studied 1,470 wells in the Greater Afram Plains region of Ghana. A total of 898 of those wells were drilled by World Vision. The study found that wells were significantly more likely to be functioning if the community had both a local water committee and fee collection system in place.

In communities where World Vision operates, local water, sanitation and hygiene committees are established to manage every new water point. The committees, comprised entirely of local residents, collect fees for the usage and repair of the wells. World Vision also provides the committees with tool kits and comprehensive training on maintaining and repairing wells when they inevitably break down. The formation and training of committees is now standard practice across many government and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and this study appears to strongly validate this approach.

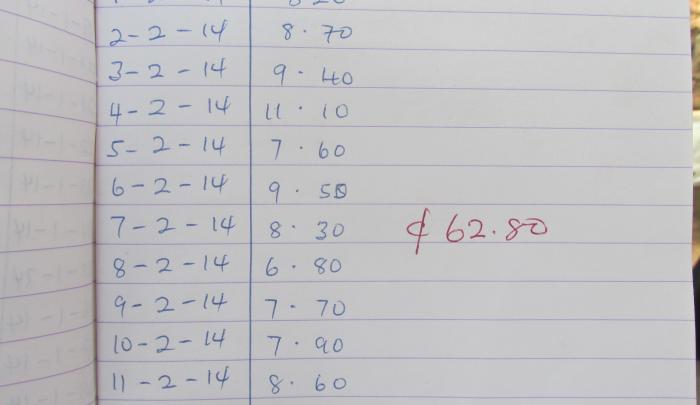

Models for fee collection vary among communities, with some opting for monthly fees and others charging a few pennies for every water jug that is collected.

The study found that 45 percent of all wells broke down in the past 12 months; however, the majority of the wells drilled by World Vision were repaired and remained operational for years to come.

“World Vision is to be congratulated,” said Bartram. “This study showed a high level of functioning of World Vision wells based on having a water committee and charging a small fee to ensure funds were available for their repair.”

More than 1,600 children die each day from diarrhea caused by unsafe water and poor sanitation and hygiene practices. This is more children than die from HIV/AIDS and malaria combined.

“Ensuring that people living in poverty have access to clean water has life-and-death implications,” said Greg Allgood, vice president of water at World Vision. “Children can’t go to school because they are sick, women walk for hours each day to retrieve water and ultimately people die from waterborne illnesses.”

Bartram and Allgood agree that local ownership and accountability as a key to ensuring that access to clean water remains after charities and NGOs leave, noting one particularly memorable encounter Allgood had with the leaders of a water committee in Ghana.

“I asked the chairman and the secretary of the water committee who owns the well, and they were clear in telling me ‘This is our well’,” Allgood said. “World Vision provided the well to them, but now it’s theirs.”

World Vision is the largest nongovernmental provider of clean water in the developing world – reaching one new person with clean water every 30 seconds. Its program in West Africa has provided sustainable access to clean water for millions of people, contributing to a dramatic reduction of diarrheal illness and trachoma and the eradication of guinea worm in Ghana.

About World Vision:

World Vision is a Christian humanitarian organization conducting relief, development, and advocacy activities in its work with children, families, and their communities in nearly 100 countries to help them reach their full potential by tackling the causes of poverty and injustice. World Vision serves all people regardless of religion, race, ethnicity, or gender. For more information, please visit www.WorldVision.org/media-center/ or on Twitter @WorldVisionUSA.

Highlights

- UNC study finds World Vision’s model of local water committees and usage fees results in nearly 80 percent of wells remaining in use after two decades