Husband’s schools save lives in Niger

Moussa Jadi, 41 days old, weighs in at a healthy 8 lbs. 3 oz., to the delight of his mother, Alima Jadi, 40, and the assistant nurse at the Rafin Wada health center in Niger’s Maradi region.

Alima says before World Vision came to her community, she didn’t know the value of eating a healthy diet during pregnancy, exclusive breastfeeding for the first year of life, and spacing births. Five of her children were malnourished, all except the last two, Moussa and his 4-year-old brother Nazirou.

“I thought malnutrition was just to be expected, but not anymore. I see a big difference with these two boys,” Alima says. “They are stronger, brighter, more active, and less often sick.”

The incidence of stunting in children under 5 has been reduced by over 7 percentage points in the Maradi villages that participate in World Vision’s LAHIA program. LAHIA, a USAID-Food for Peace-funded program in partnership with Save the Children, supports health and nutrition in children and helps families and communities achieve food security and resilience.

Village chief Ilia Ibro credits husband’s schools organized by World Vision for big changes in the community, including better access to health care, reduction in malnutrition among children, an increase in family planning, and prenatal consultations.

Traditionally, in rural Niger, women don’t make health decisions for themselves and their children. Alima’s husband used to discourage her from coming to the health center, she says. She came only when one of her children was seriously ill. Now that he’s a husband’s school member, he encourages her to bring their children for check-ups. She also comes to the center monthly for family planning.

“Before LAHIA, if a woman came to the health center there was a problem at home (with her husband),” says Ilia. “Ninety percent of deliveries were at home, too, and many women and children died.”

Tassiou Moussa’s wife died in 2000. He’s still emotional when he talks about it.

“My wife died after giving birth at home. She bled and it wouldn’t stop,” he says. Though villagers called an ambulance, it was too late. “She died on the way to the hospital; the baby died, too.”

Tassiou wants his community to learn from the past. “There was no health center, no husband’s school. We didn’t bring our wives for prenatal care. We didn’t know that women need certain food for the child to grow well. We didn’t know when to come for help,” he says.

“But not now,” says Tassiou firmly. “Now every time women come to the center.”

Husbands study new ways

Husband’s school member Inoussa Yacouba, 53, is a man on a mission.

His friend’s wife is pregnant, but she’s not going to the health center for checkups. Inoussa worries that she’s not getting the care and nutrition she needs. He and his wife, Absou, are doing their best to influence their neighbors to come to the health center.

“I refuse to accept that women deliver babies at home,” he says adamantly. “At home, it is difficult to stop the bleeding; at a birthing center, it’s easy.”

Inoussa is a passionate supporter of women’s and children’s health because he learned the grim facts of life as a husband’s school member.

- Niger has the world’s highest birthrate, with women giving birth to an average of 7.6 children. In Maradi region, where Inoussa lives, and in neighboring Zinder, the birthrates are even higher – 8.4 and 8.5 children per woman respectively.

- Niger’s maternal and child mortality rates are among the world’s worst. About 127 out of every 1,000 children under age 5 die, and 553 women die out of 100,000 who give birth.

- Less than 30 percent of women deliver their children in a health facility or have a trained birth attendant.

- Girls often marry in their early teens and begin childbearing before their bodies are fully developed.

- Because of poor nutrition, teen mothers have low birthweight babies, which sets them up for chronic malnutrition and stunting, with lifelong ill effects.

- More than 40 percent of children under 5 are chronically malnourished.

“Before (LAHIA) so many children were sick and malnourished,” says Inoussa. “We didn’t know babies should only have breast milk or that women needed special food when they are pregnant. There was no family planning here, but now there is.”

“Healthy children, healthy mothers. That’s the difference I see,” he says.

Learning to lead change

In Rafin Wada village there are five husband’s schools with 12 members each. In the whole LAHIA program there are 35 husband’s schools with about 384 members. Men are recruited into husband’s schools when their wives give birth. Inoussa is a member of Ci Gaba husband’s school, which means “make progress” in Hausa, the local language. Each school has a name and a coach selected to be a model and mentor.

School members meet twice a month to learn about maternal and child health issues. Because of all they’ve learned together, husband’s school members are strong advocates for maternal and child health with their neighbors and with government health authorities.

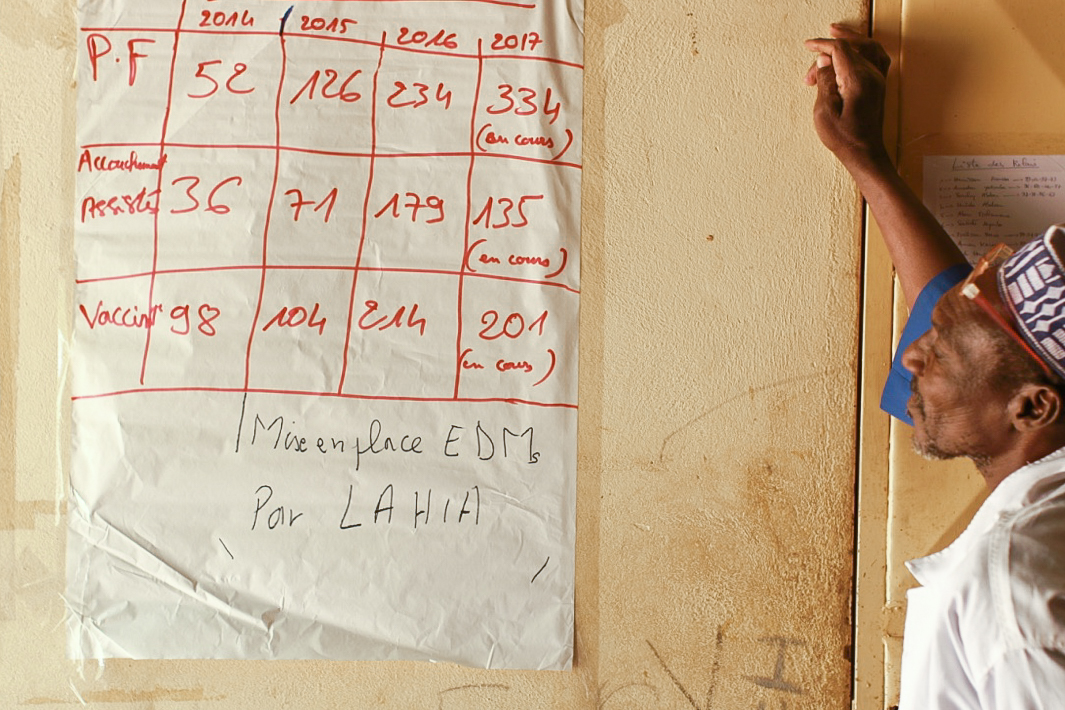

Nurse Elhadji Abou Harouna, 56, treats about 40 patients a day at the health center and advises the husband’s schools. At the door to the health center, he posts statistics for immunizations, births, and family planning visits each month. Malaria cases are down and there are zero malnutrition cases.

“When I moved back here in 2016, I was amazed at the changes,” says Elhadji, who was born in Rafin Wada. “There were husband’s schools, family planning, many improvements in health and malnutrition. Before LAHIA, there was no interest in family planning.”

Maman Harouna, 60, a leader of the husband’s schools, explains, “People in the village used to think family planning was only about avoiding more children. But in the past when we had too many children they were all malnourished.”

Maman says that since joining the husband’s schools, men have become more aware of malnutrition and more concerned about women’s and children’s healthcare and nutrition. They are glad for their wives to come to the center for injections to space births.

“Since 2014, the husband’s schools have brought a big change to this village,” says Saratou Habou, LAHIA coordinator for health and nutrition.

In addition to improvements in health, “Social relations in the community improved,” she says. “There is cohesion in the husband’s school membership and between husbands and wives. Before, you wouldn’t see a man sit near his wife or with his wife and children. Husbands and wives didn’t discuss health and family planning. Now they do.”

Saving for a better life

At the end of each month, the 60 men of Rafin Wada’s husband’s schools spread out mats under the trees in front of the health center where they meet to discuss challenges in the village and find solutions together. They each contribute 100 CFA a month (about 18 cents) to be used for village projects. They use their savings to cover health care costs for women who can’t pay to deliver at the center, even women from outside the village.

“We’ve paid the costs for 50 women,” says Maman. “We gave it to them as a loan, to pay back if they could, but 20 families couldn’t repay.” Their debts were forgiven.

When Elhadji, the nurse, told the husband’s schools that without a birthing room, women didn’t want to deliver their babies at the health center, the group bought wood and cement and built a two-room maternity center with their own labor and matching funds from LAHIA and USAID. Then they built four new classrooms for the secondary school so more boys and girls can attend.

“We are saving together to do these things,” he says, as he opens up the husband’s school money box and puts in members’ contributions. Maman is working toward government registration for an association of husband’s schools so that they can open a bank account for their savings.

The next project planned is the most ambitious for the husband’s schools. They want to pipe water from the village well to serve the health center and birthing center. They’ve consulted with World Vision and government water engineers and are making plans, setting a timetable.

“We see this being a hospital one day,” Maman asserts. Around him, fellow husband’s school members laugh and nod confidently. Where they once saw challenges and limits, they now see unlimited opportunities to make life better for their families, especially children and women.

This project is made possible by the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents of this article are the responsibility of World Vision, Inc. and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the Unites States Government.