Every child loves a good game of chase. If kids are the age when boys and girls become bashful with each other, a gender-based tag game is all the better. Grinning boys kick up dust as they playfully lunge at girls, who screech and clump together for protection, the brave ones sprinting away, laughing over their shoulders.

It’s a wholesome, energy-burning activity for members of the children’s parliament, a program created by World Vision for young people in Huanta, a city in the Andean highlands of Peru. The kids, ranging in age from 8 to 17, have just wrapped up a long meeting in a stuffy auditorium — the weekly gathering for discussing their rights, developing leadership skills, and devising campaigns to help disadvantaged children. Now, as the late afternoon light slants across the scrubby foothills, they break loose outside with boisterous fun.

Miles away and a lifetime ago for these kids, their parents and grandparents ran for their lives, chased from rural villages by a brutal Maoist group known as Sendero Luminoso, Shining Path, who used violence and intimidation in their campaign to overturn the government. They also fled from menacing military soldiers intent on crushing terrorism at any cost. The conflict, raging through the 1980s and 1990s, killed nearly 70,000 — 75% of whom were indigenous people, like these children.

World Vision in Peru, despite its own tragedy, began working in the region again once key Shining Path leaders were captured. In 1996, World Vision helped uprooted families who settled in the city organize themselves into what is now a powerful local entity, the Association of Displaced Families in the Province of Huanta, and launched a sponsorship project.

World Vision and the Association of Displaced Families in the Province of Huanta, backed by a legion of child sponsors in the United States, have spent the past two decades creating an environment where children can thrive. Along the way, families have become empowered to take over the work themselves. In September 2015, World Vision will close the Huanta project — a natural conclusion to the years of collaboration and a standard practice in every community around the world.

Young people — the first generation to grow up in peace — confidently claim their place in advancing the progress.

“World Vision is closing, but we will continue. We will do even better things,” says 13-year-old Angel Gustavo Luza Lapa, vice president of the children’s parliament. “We will change our communities.”

Past and contrasts

Huanta’s children know their city, dubbed “Emerald of the Andes,” as a place where the past and present companionably mix. Women in traditional Quechua fedoras and pleated skirts walk with produce bundled in their embroidered shawls, gazing at their smartphones. Colorful moto-taxis compete on the narrow streets with full-size pickup trucks and sedans. A colonial-era Catholic Church presides over the main square, while a 50-foot, gleaming white Jesus statue, built in 2006, overlooks the city with arms outstretched.

This provincial capital was little more than a dusty town, the last stop before ascending into the mountains, when the Shining Path started rampaging through the countryside in the 1980s. The movement originated in this region and pursued the Maoist ideal of a peasant revolution that would eventually take over the country. As rebels became increasingly violent and Peru’s military ramped up its counterterrorism measures, indigenous Quechua people were caught in between.

There’s little evidence of these times, even in Huanta’s tranquil, tree-lined city cemetery. Rows of crypts rise five high and dozens across in blocks arranged by date, with the cause of death seldom indicated. Yet a set of six nearly identical graves of young men who died on the same day, Aug. 1, 1984, gives pause. The men were worshiping in an evangelical church when soldiers dragged them out and shot them, ordering the other congregants to keep singing.

Among the few overt signs of the conflict is a mural near the soccer stadium, depicting Quechua women toting a banner that promises to “reap the truth” and “build reconciliation for the peace of loved ones.” The mural’s proximity to the stadium is deliberate. In the early 1980s, the military turned the stadium into a torture chamber for suspected terrorists. Some detainees ended up in mass graves; others were never found.

Today, spectators streaming out of the stadium after a soccer match pass the mural with barely a glance, and if hearts are heavy it’s likely due to the final score.

For children born after Shining Path leader Abimael Guzmán’s capture in 1992, terrorism has faded into the background. Free of the pain that lurks just under the surface for their parents, Huanta’s children also have opportunities that were well out of reach for previous generations — and they make them count.

As Karen Diaz Curo, 13, walks home from San Francisco de Asís High School, the paved streets give way to dirt roads and pockmarked adobe structures emblazoned with mayoral election slogans. She lives in Hospital Baja, one of 17 ramshackle neighborhoods that swelled with displaced families during the violence. The houses here are the same color as the ground, as if the dwellings heaved themselves up out of the earth.

Climbing a rickety wooden ladder to the bedroom she shares with her brother — a One Direction poster marks her side — Karen shows off her academic medals and the books she’s reading, including Ernest Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms. She points out the bed and a canvas wardrobe she bought herself with prize money from a singing competition.

Karen’s father, Simeon Curo, 47, built this house little by little after settling in Huanta 20 years ago. He grew up in rural Pallcca, in the mountains. “We had to leave because of the terrorism,” he explains. “[Shining Path] came to villages in the evenings and killed people.” After his uncles were murdered, the family escaped on foot.

Simeon, a moto-taxi driver, has worked to provide a better life for his eight children — several of whom are high achievers. Rony, 22, got involved in the children’s parliament when it began in 2002 and still serves as an adviser when he’s in Huanta on university breaks. He encouraged his younger sister Karen to join.

Last year, Karen was elected president of the group. “At the beginning, I didn’t want to be a candidate,” she says, explaining that she used to fear public speaking. “My brother encouraged me: ‘Go, go, go.’”

Now she’s an example for younger brother Miker, 10, who pipes up: “I’m going to be the future president of the children’s parliament.”

Without missing a beat, Karen replies, “I’m going to be the future president of Peru.”

Confidence and hope

Such ambition was unthinkable for families who sought refuge in Huanta in the 1980s, arriving with little more than harrowing stories. A grandmother wept while recalling the coldblooded killing of her daughter, shot while holding her baby as her other children stood nearby. A mother told of sending her children to hide in the cornfields during terrorist attacks. A young father described soldiers lining up 16 people from his village and gunning them down. Many people could not explain why their loved ones had been killed, either by the Shining Path or the military — one man simply saying, “Things were very violent.”

Quechua people, who from the days of the Inca had lived and farmed in the highland villages, found themselves completely out of their element in the city. They had to work menial jobs to support their families. Settling at the margins of Huanta, where there were no municipal services like running water and electricity, they built their homes with their own hands. Their children were barred from most city schools.

Yet many did not return to their villages once the violence subsided. Some couldn’t revisit the scenes of such horror and heartbreak. Others hoped to take advantage of the city’s opportunities. But they all lost out on government compensation for those who did go back.

It required more than quick fixes or handouts to help them. “What an armed conflict leaves as a consequence is mistrust, suspicion, and doubt,” says Victor Belleza, who started World Vision’s ministry work in the province. “We had to restore relations, build confidence and hope.”

Confidence sparked when people participated in World Vision programs and training sessions, elected leaders, and learned how to lobby the local government for utilities, paved roads, and schools. “We were very shy people. We didn’t know how to talk,” says Vilma Hurtado Paredes, the current president of the displaced families’ association. “World Vision helped us behave as citizens.”

Confidence grew as mothers acquired nutrition training and basic health skills, removing one obstacle after another hindering their children. Workshops helped couples acquire the confidence to move beyond the machismo culture, enabling women to share their ideas and work as equals with men. Gladys Condor and her husband, Emiliano Perez, modeled this as she directed a mothers’ organization, thousands of women strong, while he served as neighborhood president. “In a workshop, I learned to be a good husband,” Emiliano says. “I encouraged my wife to be a leader.”

Confidence spread like wildfire as cards and letters from the U.S. poured in — child sponsors affirming thousands of Huanta boys and girls that they mattered. Joe Ramos Diaz, 20, keeps a letter from his sponsor that says, “I’m proud of you. I have seen you grow up.” The sponsor would be even more proud to see Joe today, striding across the sprawling, cactus-studded campus at San Cristóbal of Huamanga National University. He’s studying agronomy with a goal to help rural farmers improve their harvests.

Hope arose as the hard work began to pay off, not just in physical changes to the community, but in the way people viewed themselves. “Many people used to think that they had to live in poverty and discrimination, and that was to be the reality for their children and the children of their children,” explains Victor. “Sponsorship changed that. It helped people see themselves as people with potential, people with values.”

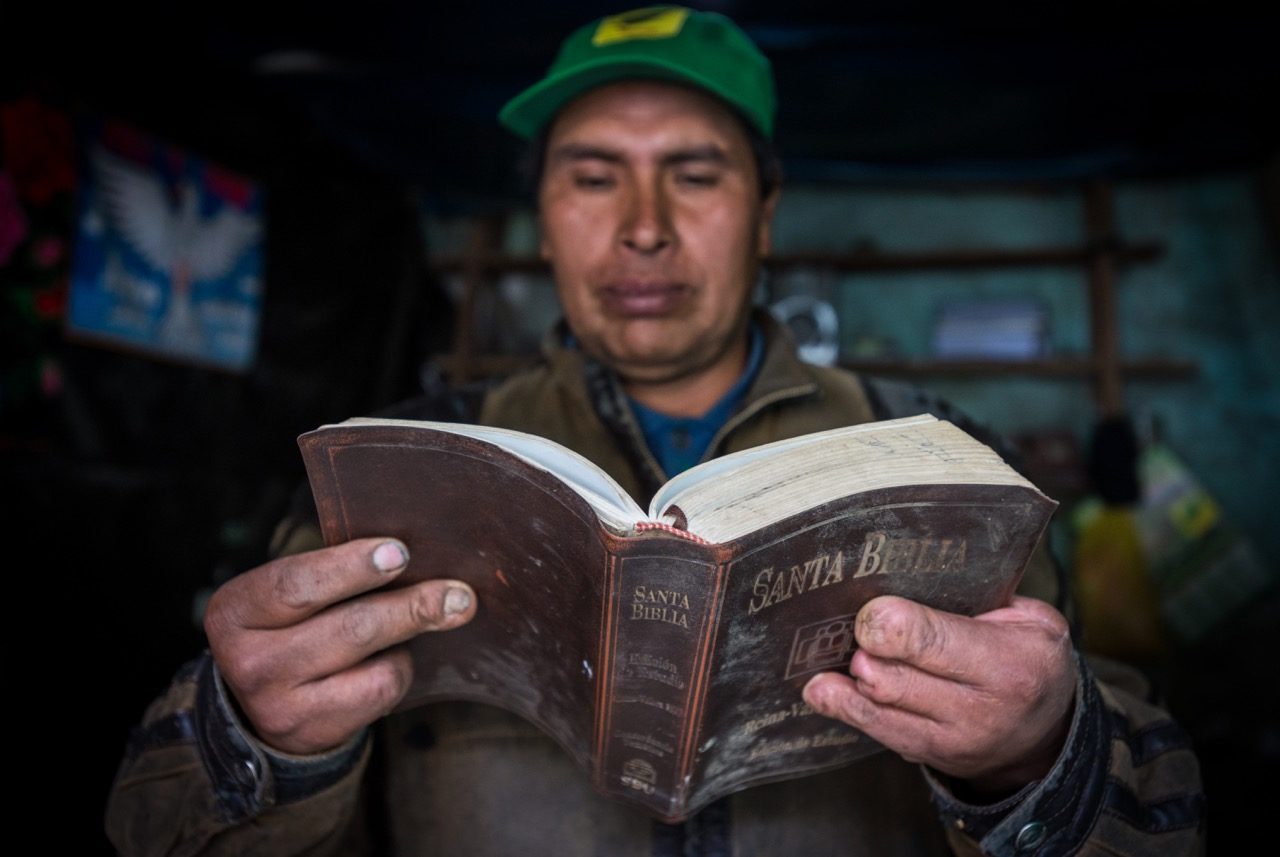

Above all, hope emanated from the assurance of God’s love, in part due to World Vision staff’s witness through their lives and words. Maritza Flores, Huanta project coordinator from 1998 to 2007, talked constantly about God and the guidance found in the Bible with families who were nominally religious or hanging onto traditional beliefs. “Maritza taught us how to pray,” says Emiliano, a simple statement repeated often among displaced families.

Maritza, who by all accounts personified the virtuous woman in Proverbs 31:10, survived a serious car accident in 2007 only to succumb to breast cancer about a year later at age 41. The petite woman with a hug for everyone remains a vivid presence in Huanta, often mentioned in conversation, her photo tacked up in people’s homes. The auditorium where the children’s parliament and association leaders meet is named after her.

Her legacy lives on in young people like Joe, the agronomy student. “I talk to God,” he says. “I feel that God answers me. Sometimes when I ask him about something, someone gives me advice — that’s the answer.”

Vocation to serve

Joe’s younger sister, 15-year-old Luana, finds answers in the Bible. As an antidote to her exhausting life — serving as secretary of the children’s parliament, maintaining top marks in math, and helping her divorced mother around the house — she leans on Matthew 11:28. “If you have problems, anything you are bearing, put it in the hands of God,” she says. “Then you will be peaceful and can go on in life.”

Luana knows where to place her burdens. She also knows, thanks to the children’s parliament, where to direct her opinions. A new expectation for Huanta’s children is that authorities will listen when they speak.

Though soft-spoken, the teen knows exactly what she’d say to her country’s president if given the chance: “Peru has an education budget of 4% or 5% of the GDP, and I would ask him to raise that percentage,” she says.

Luana helped organize the Huanta chapter of an emerging governmental entity for youth, the Advisory Council on Children and Adolescents. In that capacity, she traveled last year to Lima, the capital, and met with government ministers to discuss issues facing vulnerable children in her region. “I like to give my opinion,” Luana says, taking a break from bustling around her house in the Hospital Baja neighborhood, just a few doors down from Karen. “But what I like best is to participate.” She cites the children’s parliament campaigns that reach out to other kids in need.

This past Christmas, they raised money through movie nights, selling vases for gravesites, and other activities in order to put on a party for children in a village high in the mountains. The young leaders hoped to encourage these forgotten children by delivering treats and toys and sharing the story of the birth of Jesus. Of course, the effort required exhaustive planning, time away from homework and chores, and tricky travel on winding, rock-strewn mountain roads — all completely worth it to Luana. “We do this because of love,” she says.

Children’s parliament facilitator Romulo Aguilar Baca notes that kids like Luana have more than skills and abilities. “They have the vocation to serve,” he says.

Joel Quispe Diaz, 22, a pensive young man with soulful eyes, uses his art to evoke the pain of the past — his grandparents were killed by the Shining Path — and bring awareness to the problems of the present.

Joel’s father abandoned him when he was 3, and his mother died before he finished high school. While living for a time with an abusive relative, he carried heavy packages and sold popsicles in the market to earn a few nuevos soles. Eventually, an aunt took him in, and he joined the children’s parliament, where he learned about his rights as a working child.

Sponsorship from age 7 to 14 enabled him to stay in school, and during those years he began to dream about becoming an artist. Today, it’s his reality. Studying at the Fine Arts School of Ayacucho, about an hour’s drive from Huanta, he lives in classic “starving artist” style in a tiny room, where art supplies and paintings nearly crowd out the narrow bed.

“I can express my feelings through my paintings,” he says. “It’s like making a poem with colors.”

One captivating piece shows a Quechua mother’s face surrounded by a cross, a skull, a torn Peruvian flag, and a bloody figure lying facedown — all against a deep red backdrop. Joel, too young for firsthand experience of the Shining Path, draws on his family’s loss and distills the devastation of the period as only an artist can do.

Another deeply personal painting, depicting a dejected, barefoot girl, is one of four pieces for Joel’s thesis project, which aims to raise awareness about working children.

Alleviating their suffering is his priority, now and in his future career. “When I see these children, I see myself reflected in them,” he says. “When I see a child crying, that affects me.”

Joel is on his way; another former sponsored child has already arrived. Denisse Pariona Lunasco, 24, has served as an adviser to Huanta’s mayor for three years — an elected position and a prime spot to influence legislation affecting children.

Less than a decade after she first visited the mayor’s office as the children’s parliament president, she went back as the youngest adviser ever hired. Now the determined young woman eyes the photos of mayors throughout Huanta’s history that hang in the municipal building and visualizes herself as the first female face in the gallery.

Of today’s child leaders such as Karen and Luana, Denisse says, “They are going to be successful. Not only that — because of World Vision working with them, they are eager to go on working for the common good.”

Home in their hearts

Billboards around Huanta convey the message: “El convenio con WV culmina … AFADIPH continua”— the agreement with World Vision ends; the Association of Displaced Families in the Province of Huanta continues. Gradually World Vision’s orange logo has been replaced with that of the Association of Displaced Families in the Province of Huanta, cartoon faces of a boy and girl. The point is clear: The good work of the past two decades won’t end just because World Vision is leaving—more can be done for the community’s children.

Who better to forge ahead than those who have walked this far? These transplanted citizens, formerly such timid people, are now organized, confident, and equipped to represent themselves in the halls of power. “World Vision has taught us when we were babies, and now we are grownups,” says Erineo Lapa, 55, president of the Cedropata neighborhood and proud grandfather of child leader Angel Luza. “We are trained and can lead by ourselves.”

Huanta, once just a refuge, is now home in people’s hearts. It’s where opportunities reside — good schools, a strong faith community, healthy influences like the children’s parliament. It’s where their children run in elections or on the soccer field rather than running for their lives; where kids can chase their dreams and face authorities without fear.

And now, it’s only a question of how far they can go.

“Many changes have happened in these years,” says Erineo. “Many young people have taken advantage of the help. They have become professionals, shining their own light.”

A new beginning after loss

Shining Path violence hit home for World Vision on May 17, 1991, when two organization executives, Norm Tattersal and José Chuquin, stepped out of a car on a Lima, Peru, street into a hail of machine-gun fire. Norm, a Canadian, was killed instantly; José, from Colombia, died 12 days later. In July of that year, another blow: Three Peruvian staff members and a community leader disappeared. World Vision, which had operated in Peru since 1965, shut down.

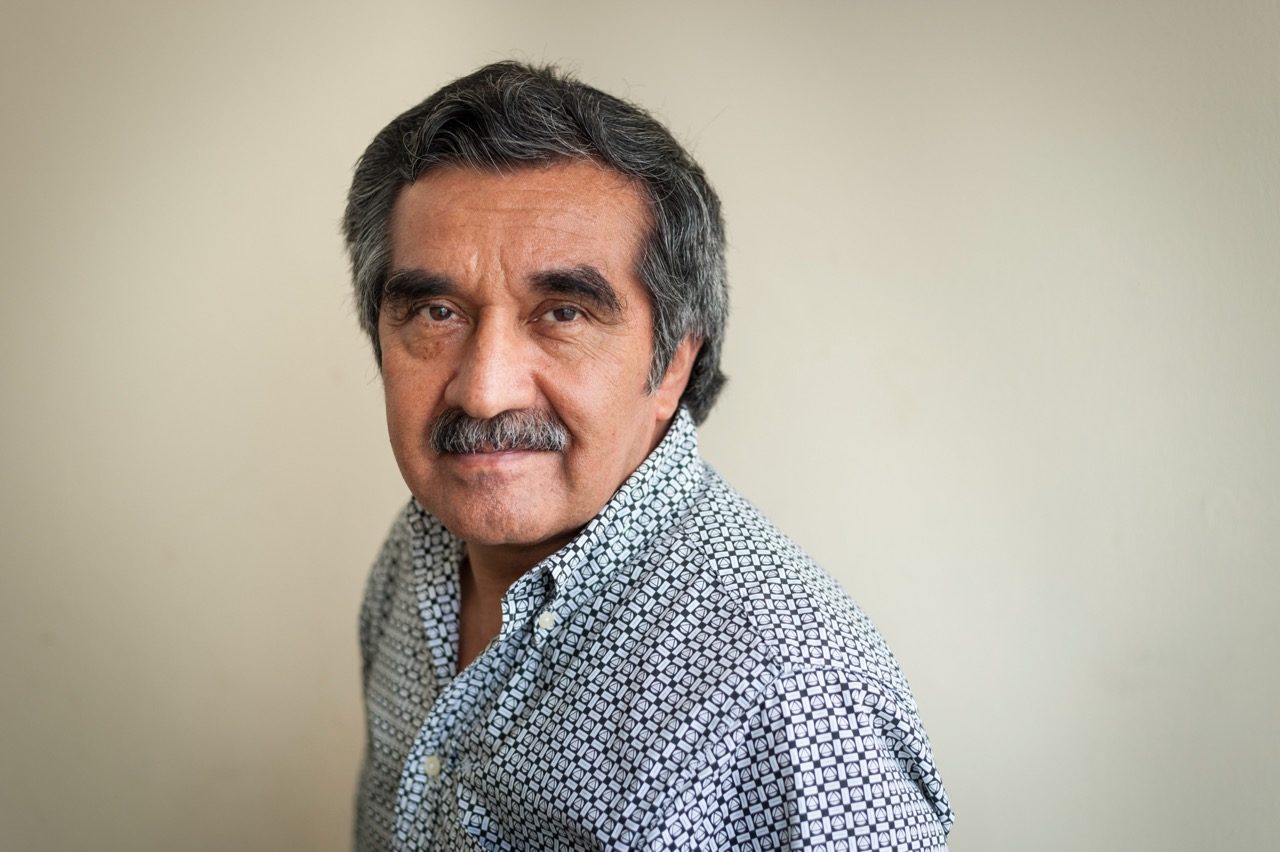

Following the Shining Path’s defeat, the office reopened in 1994. Caleb Meza, the new national director, immediately faced a quandary: Former employees were suspected to have ties to the terrorists, yet he was legally obligated to rehire them, should they apply. He posted the reopening announcement in a newspaper for one week. “It was a very difficult week for me,” he recalls.

No former workers responded, freeing Caleb to call trusted people to his side — Christians with an extra dose of courage required to work in still-dangerous areas of the Andean highlands.

Ministry in post-terrorism Peru was hardly business as usual. Caleb grasped greater responsibility to care for the disenfranchised — and greater opportunity to draw on the people’s own potential. “The programs in the past were only about welfare,” he says. “I wanted a proposal that would go from social assistance to social action, from social action to public influence.”

World Vision’s long-term, holistic approach bore fruit in Peru’s highlands. “It’s more than education, more than health,” says Victor Belleza, World Vision’s ministry quality adviser, who helped launch the highland projects. “It’s about the person. It’s about the children. You are with them to build their lives and their future.”