Citizens of

NOWHERE

By Kari Costanza | Photos by Jon Warren

Karen Homer and Himaloy Joseph Mree of World Vision in Bangladesh contributed to this story.

Five-year-old Jannatul Firdous is deep in thought. How best to describe the meaning of her name? Jannatul Firdous means heaven — the best heaven — so she wants to get it right.* “Heaven is a place where children can play,” she begins as her 26-year-old mother, Salima**, gazes at her with a sweet half-smile. “There are many flowers,” continues Jannatul. “There is a big pond of water. Heaven is a happy place.”

Camp 13, where Jannatul now lives, is no heaven. Children play in the dirt, kicking up dust that floats in the hot afternoon air. It’s a far cry from the lush, green countryside surrounding the home she fled in Myanmar. Here, there’s no playful splashing in big ponds. Instead, Jannatul must lug heavy metal water containers from a pump up a steep hillside staircase that leads to her family’s makeshift shelter. In Camp 13, some sweat under a hot sun, breathing in the diesel fuel stink of trucks loaded with bamboo poles. Amid the cacophony of clinking shovels and pinging hammers, they lay bricks and fill burlap bags to shore up steep hillsides to prepare for the coming monsoon season.

Jannatul lives in the world’s largest and most densely populated refugee camp in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh. Of its nearly 1 million residents, more than half are children. Most of the people here are Rohingya, a persecuted, predominately Muslim-minority group from Myanmar, who have faced discrimination in Myanmar over several decades, including the denial of citizenship. In August and September 2017, more than 740,000 Rohingya fled to Bangladesh, driven from their homes by extreme violence in Myanmar’s northern Rakhine State. They joined about 200,000 Rohingya who had previously fled here.

*Jannah is often translated in the Qur’an as “heaven.” Jannatul Firdous is Islam’s highest level of heaven.

**Name changed for protection

A World Vision nutrition center atop a hill in Camp 10

Camp 13 is one of 33 sprawling subsettlements within the “mega–camp.” Squalid and overcrowded, it is home to 41,000 people who are citizens of nowhere — the antithesis of the happy place Jannatul dreams of. What can be done for girls like her born to live a full life? The answer lies in World Vision’s three areas of focus in the camps: provision, protection, and partnering with the host community. World Vision staff in Bangladesh work to meet refugees’ basic needs and those of the surrounding community and help to ensure that children and their parents are safe, and their rights are protected.

Provision: Tackling the basics

The mass exodus of the Rohingya from Myanmar is a story of hell on earth. Girls and women, especially, arrived in Bangladesh with both physical and emotional scars. A 2018 United Nations High Commission for Refugees report titled “Culture, Context and Mental Health of the Rohingya Refugees” details how women were molested, raped, and forced into prostitution in Myanmar.

When violence erupted in their village in August 2017, Salima’s family of five became separated. “Jannatul was with me, but I didn’t know what had happened to my husband and my [other] children,” she says. “Later, I saw them dead.” Mohamed, 30, was shot; their son, 2-year-old Hafej, and daughter, 1-year-old Kalima, were stabbed to death. Her expression clouded by sadness, Salima holds out her phone to show a photo of Kalima and Hafej, smiling and pressed up against their big sister, Jannatul.

Provision — meeting basic needs — was the goal when World Vision began helping refugees in August 2017. Jannatul and Salima were among the first beneficiaries. “World Vision gave me shelter,” says Salima. The shelters built by new arrivals were erected hastily, made from chopped-down trees and covered with tarps handed out by the U.N. Then in April 2018, World Vision provided bamboo poles, cement, and additional tarps to fortify the shelters against the seasonal monsoon rains.

Salima was one of 150,000 people campwide who received essentials like hygiene kits, cooking equipment, and feminine hygiene products — desperately needed by people who arrived with little more than the clothes they wore.

Water was another essential need. In Camp 13, World Vision installed deep tube-wells, pumps, and latrines. By the end of 2018, 158,000 people had access to water and sanitation services in Salima’s camp and 12 others.

Urgent health issues were also addressed. A study by the Bangladesh Ministry of Health revealed that 10% of the children under the age of 5 in the camps had moderate acute malnutrition, which can lead to death if left untreated. World Vision, working in partnership with the World Food Programme opened malnutrition prevention and treatment centers in three camps to reach more than 13,000 at-risk children with supplementary food.

World Vision’s response in 2018

264,881 people reached with life-saving humanitarian assistance

1,720 children each week on average benefited from protection activities

158,000 people reached with clean water and sanitation services

30,535 children and mothers received nutrition support

44,280 people reached with upgraded shelter kits

150,000 people received essential items (hygiene kits, cooking equipment, baby supplies, feminine hygiene products)

22,500 people benefited from cash-for-work activities

920,000 total people for whose protection and rights World Vision is advocating, including their voluntary, safe, and dignified repatriation to Myanmar

No one in the camp has money, and it’s illegal for Salima and other refugees to work outside the camps. Instead, she participates in a World Vision cash-for-work project that provides short-term jobs for refugee men and women to build much-needed roads, bridges, and drainage systems in the camp. Salima helps fill burlap sandbags that will be used to prevent landslides during the annual monsoon rains that turn the camp into a muddy, hazardous mess. The money she earns each day, 300 taka (about US$3.50), will buy Jannatul something special — a chicken for dinner or bananas to supplement their daily diet of rice and lentils that is provided to all refugees by the World Food Programme.

Salima didn’t expect this assistance. When they left Myanmar, Salima says, “We were just trying to save our lives. We didn’t think we would get support like we do now. For everything, I am grateful.” As members of an organization rooted and founded in faith, World Vision staff undergird their labor with love — love that is evident to Salima. “World Vision people are good and kind to us,” she says.

Jannatul is one of nearly 3,000 children who attend World Vision’s 12 Child-Friendly Spaces in six camps — each one an oasis of fun. By providing psychosocial care and structured activities, Child-Friendly Spaces support kids whose lives have been turned upside down by emergency situations. The spaces are now being transitioned into learning centers, giving children an opportunity for informal education.

Situated in the heart of the camp, Jannatul’s Child-Friendly Space is a lively, happy — often noisy — space that’s painted a cheerful orange. The children named this space themselves — Surjoful — after something they’d left behind in Myanmar: sunflowers. Jannatul shines at the Child-Friendly Space, singing, dancing, and reciting rhymes such as “Rain, rain, go away” in English.

The energetic little sprite is a staff favorite, says her teacher, Farjana Faraz Tumpa, 20. Jannatul doesn’t miss class. Some kids prefer to stay with their mothers, lining up for daily relief supplies. But Jannatul is an eager learner. Says Farjana, “When I teach [the children] something, she follows me very carefully.” Farjana holds Jannatul’s mother in great esteem, too. “She is a very good lady. Whenever we call a parents’ meeting, she comes. She has only one child, so she is very careful with her.”

Partnering with the host community

Farjana is a member of the host community of 330,000 Bangladeshis in Cox’s Bazar district, home to a fishing port and a tourism destination that features the world’s longest natural sea beach: 75 unbroken miles of gently sloping sand. Two years ago, Farjana watched as hundreds of thousands of refugees converged on 8 square miles of green hills — about six times the size of New York’s Central Park — and began cutting down trees for shelter and firewood.

While the Bangladeshis gave what they could to the distressed Rohingya — many of them leaving their dinner tables to share food with exhausted travelers arriving at night — the new arrivals caused stress. People in the area were already poor, even by Bangladeshi standards, with 33% living below the poverty line and 17% below the extreme poverty line. There are always tensions when people compete for finite resources such as firewood, land, and water. They see big trucks moving into camp, laden with relief supplies, and wonder why their own families still don’t have enough to eat. So assisting host community members became an essential element of World Vision’s work.

World Vision hired hundreds of local residents like Farjana to run its programs in the camps, providing income for locals and helping build understanding between the two populations. Soon World Vision will also begin a child sponsorship program — a proven poverty-fighting approach — in Cox’s Bazar. Sponsors in the United States will be able to connect with a child in the host community, providing support for essentials like education, health, and economic opportunities for their parents.

To help protect the environment and prevent conflict, World Vision operates 42 community kitchens, where up to 1,000 refugee families can cook each day in shifts. Cooking in a safe space on gas stoves, rather than using firewood, keeps people from cutting down trees. The community kitchen in Camp 19 smells of delicious food. “I love to cook here,” says 22-year-old Muchena, also a refugee. “Even if I don’t have anything to cook, I come to have fun with other women. The kitchen is like our home.”

“The kitchen is like our home,” says Muchena. World Vision operates 42 community kitchens, where more than 1,000 women can safely cook and socialize daily.

Community kitchens are bright spots in an otherwise harsh existence for women like Muchena and cash-for-work programs give a boost to mothers like Salima, although she misses the days when she could just be a stay-at-home-mom. “If I didn’t have to work and if I could take care of my daughter [all the time], I could create a heaven on earth,” says Salima. And with that, it’s time to sing Jannatul to sleep. The best part of the day has arrived, a time to close her eyes and pull her daughter close, tasting heaven for a moment in a place that’s anything but.

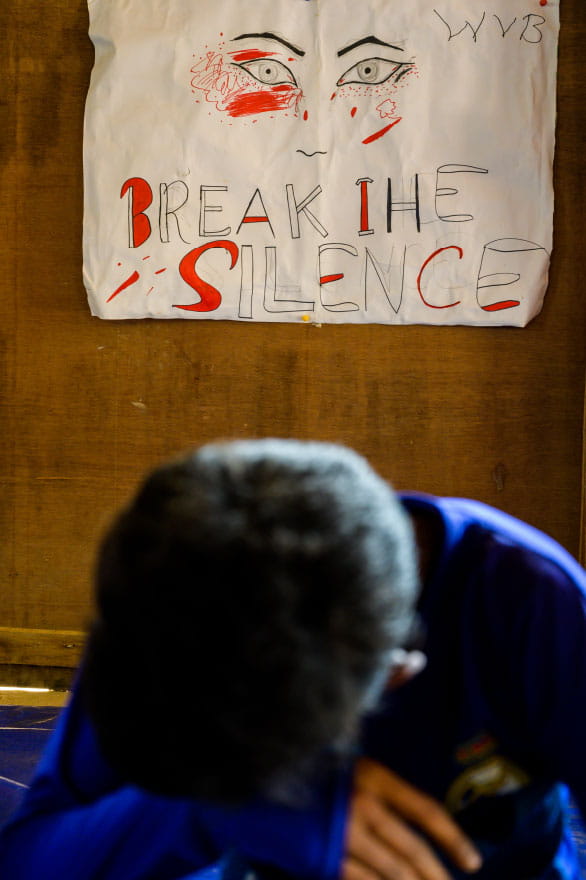

Protection: Preventing violence against women

Preventing violence against women is an important component to World Vision’s work with the Rohingya. This involves keeping children and their families safe in the camps and advocating for their rights.

Women and girls are particularly vulnerable. Women in the camp have reported physical and sexual assault, psychological abuse, and forced marriage. Of the reported cases of gender-based violence, 71% of the incidents occurred in the survivor’s home, and 74% of the total number of cases were committed by intimate partners.

In Camp 13, World Vision runs a safe space for women where they can talk about such issues and get help from trained counselors. Salima and her neighbors learn what gender-based violence is, how to protect themselves, and get professional help should they need it. Men and boys are also engaged so they can be part of the solution.

Ata Ullah, once an eighth-grade teacher in Myanmar, now works with World Vision teaching gender-based violence prevention classes for boys and men.

“It is important to stop conflict between people,” says Ata, 27, sitting cross-legged and cradling his 18-month-old son on his lap. “What World Vision is doing about education and violence is important. With violence, the community cannot have a better life.”

Ata arrived with his wife in the huge influx of Rohingya in the fall of 2017. Crossing the Naf River by boat, he carried his newborn son high over his head, struggling to reach the shoreline of Bangladesh. Around them, crescent-shaped boats loaded with too many passengers capsized in deeper waters, drowning women and children.

Ata and his 23-year-old wife, Sahnewaj, recently welcomed their second child, Rahaena. “It was difficult,” says Sahnewaj about being pregnant in a refugee camp. “I fetched water from down the hill and climbed back up. I couldn’t breathe for a while. I felt really bad.” When she went into labor late at night, it was unsafe for her to leave their shelter, so she delivered the baby at home, assisted by a neighbor rather than a nurse. Despite the challenges, Rahaena arrived at 2 a.m., and she is adored by her parents. “She is beautiful,” gushes Ata.

Sahnewaj has seen a transformation in her husband since he started helping other men to change the way they view and behave toward women and girls. “Sometimes he would get mad at me, but now he’s different,” she says. Ata agrees: “I didn’t treat my wife well earlier. I have learned to treat her equally. We have equal rights in our family.”

Ata particularly wants to help boys in the camp change their attitudes toward the women in their families. Thirteen-year-old Sirajul is one of 80 boys who recently finished World Vision’s two-day course on preventing gender-based violence, led by Ata. They learned how inequality between men and women and boys and girls breeds injustice and physical and sexual violence.

“We are really concerned about our sisters,” says Sirajul, sitting next to his sister Samira. “The women are not safe.” He knows that Samira is vulnerable to abuse in the camp. She leaves the house only to visit the latrine. At home, she steers clear of the front room, where she could be seen. “We are shy of men here,” she says. “That’s why we stay in the back.”

It was different for Samira in Myanmar. While she had to live by the norms of a culture that keeps girls at home from the time of their first period until they are married, there was space to be free. “I miss my home,” she says. “I could go outside of my home and run. Here, I just have to stay in this room.” She worries about the heat. “Summer is coming,” she says. “I don’t know what it will be like here.” She misses the flowers, especially the marigolds. “In our homestead, just before the fence, we planted many flowers and had fruit trees,” she says. They would go out in the cool of the evening to tend to the flowers and trees. Now Samira is trapped inside.

The workshop helped Sirajul see his sisters, including 16-year-old Fatema, in a new light. “Earlier, when I asked for food and they couldn’t make it, I scolded them,” he says. “Now I don’t. They asked me, ‘What happened to you? What did you learn at that center?’”

Sirajul loved the classes and the teachers, like Ata. “We like World Vision. They gave us an opportunity to learn,” he says.

As a teacher, Ata is concerned for the boys like Sirajul. The curious, talkative, thoughtful boy was in the top quarter of his class of 80 in Myanmar and misses going to school. Formal education is not permitted for the 540,000 children and youth living in the camps. Almost half of the children ages 3 to 14 years do not have access to any kind of learning, nor do 97% of adolescents and youth ages 15 to 24 — leaving them vulnerable to child marriage, child labor, human trafficking, abuse, and exploitation. World Vision is opening 21 learning centers for adolescent boys and girls — the first will be in Camp 13.

“Without education, they must learn something to earn a living,” says Ata. “If they don’t have education, they may be involved with theft or robbery.”

With his skills, experience, and passion for people, Ata is wasting no time in addressing this urgent need. Learning is critical for the next generation of Rohingya. Ata stays focused on what matters — youth and his family. “When I have time, I visit my relatives,” he says, smiling. “There are many in Camp 13.” A breeze blows through the family’s small house, rustling a red curtain and creating a rosy glow that dances across his wife’s face. Her beauty shines through the darkness. Camp 13 may not be heaven, but for now, it is home.

Video Library: