Twenty-four years after the Rwanda genocide, children like Julius — a top student in his school — continue to die from poverty and lack of clean water.

As Rich Stearns wraps up his tenure as World Vision U.S. president, he is dedicated to ending this needless loss of life, in Rwanda and around the world.

* * *

The room on the second floor of the Kigali Genocide Memorial in Rwanda’s capital is quiet, tastefully arranged, and thoroughly gut-wrenching. This is the Children’s Room, featuring photographs of small boys and girls along with their names, single-digit ages, likes and dislikes — and the brutal ways they died during the 1994 genocide.

It’s not easy to face the horrific loss of precious young lives. But I’ve learned it’s necessary. A broken heart motivates change. That’s why Rwanda, through its memorials and a weeklong period of mourning each April, continues to confront its national tragedy in which 800,000 people, young and old, died during 100 days from April through June 24 years ago.

Children still die needlessly in Rwanda, but not from ethnic violence. The killer is more benign but just as effective: poverty. Unsafe water plagues about half the population.

Last November in Gatsibo district, a 17-year-old boy named Julius waded too deep into a dirty pond to get water. He got stuck and drowned. Julius was a standout student in his community. The headmaster of his school says, “Our country lost a very strong young man. His performance indicated that he would make a great contribution to Rwanda — his marks were above distinction.”

Julius died before finding out that he scored high enough on his national exam to qualify for a scholarship to a top-notch college.

The pond that snuffed out Julius’ promising future was his family’s only water source. Francisca, Julius’ heartbroken mother, appealed to me, “Please help us get clean water because we don’t want any more children like Julius to die.”

That’s what I intend to do. In my last months as World Vision U.S. president, I’m committed to making sure every person in our Rwanda project areas will have access to clean water within five years. This is part of World Vision’s goal to provide clean water for everyone, everywhere we work by 2030 — Rwanda is where we’ll finish the job first.

We’re working with the Rwandan government, which has its own ambitious plan to bring clean water to all citizens by 2024. “Your goals are our goals,” Prime Minister Édouard Ngirente tells me.

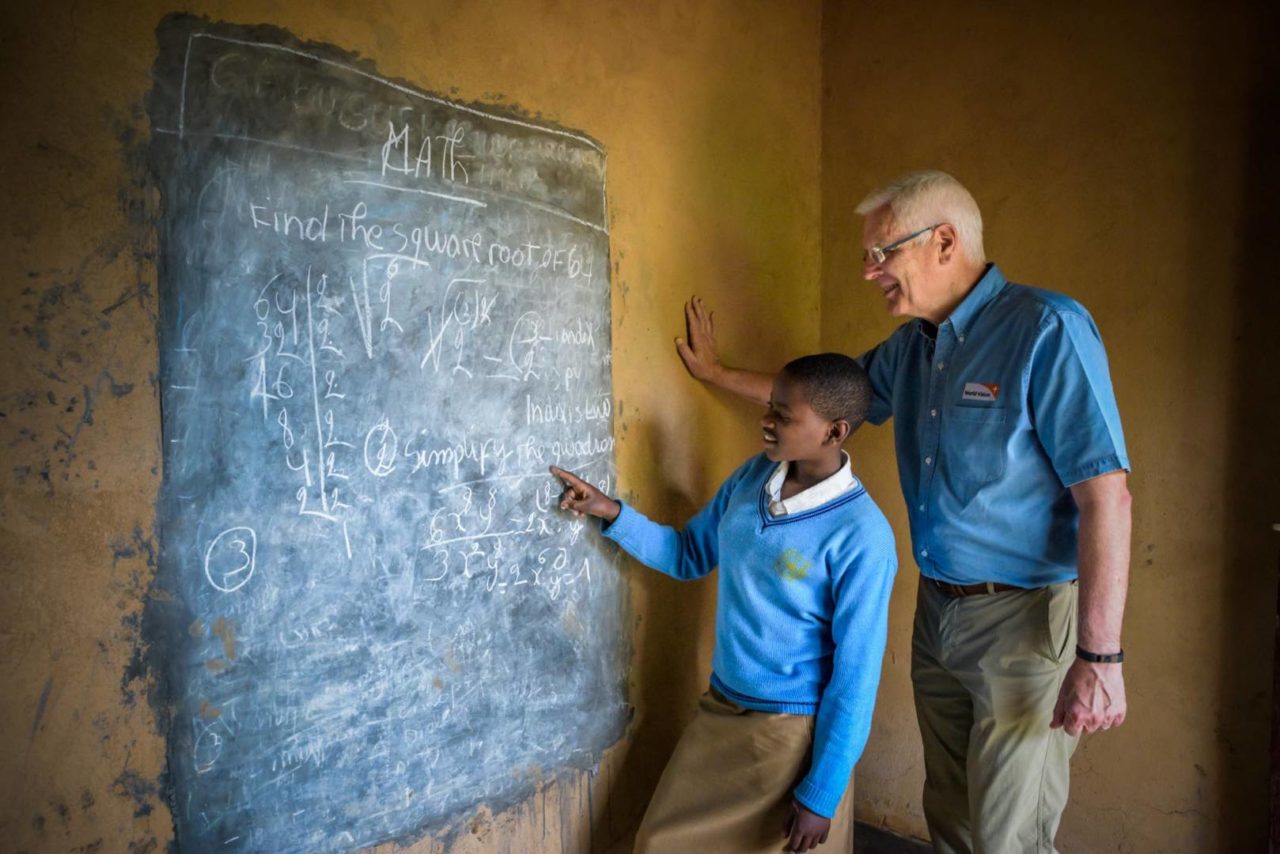

This partnership has already brought change in Gicumbi district, where a new 6.8-kilometer pipeline provides clean water for about 8,000 people. There I met 15-year-old Isabelle, a standout student like Julius had been. Her headmaster and teachers rave about her. I watched in amazement as she vigorously scribbled on a chalkboard in her home, solving a complex calculus problem and smiling the entire time.

The new water tap is a short walk away, so Isabelle can quickly fill up in the morning before school and spend her time afterward on homework. These days she doesn’t get sick and miss class as she used to from drinking water from a contaminated stream.

Isabelle and Julius: two exceptionally brilliant, beloved children, one alive, one dead — and the difference is clean water.

But Rwanda is hardly the only place where this happens. Every day, more than 800 children under age 5 worldwide die of diarrhea, which as we know is completely preventable with clean water and proper hygiene. These are utterly needless deaths of precious children. We must face this.

And then we must change it. It’s not only the job of large organizations and governments to solve the global water crisis. We need everyone to push in the same direction. Most of us easily spend $50 in one restaurant meal or a trip to the grocery store — that’s how little it takes for World Vision to provide lasting clean water for one person.

Are you willing to change a life? Next month is World Vision’s Global 6K for Water, an event mobilizing water-wealthy people like us to walk or run the typical distance developing-world women and children have to go to get water. Every person who registers saves a child from the desperation of dirty water.

By participating, we protest the needless loss of precious children. With each step, we signal hope to brokenhearted mothers like Francisca.

Read more about World Vision’s Global 6K for Water.

Read more from the World Vision blog.

Comments